How Do You Become What You Cannot Yet Understand?

How Do You Become What You Cannot Yet Understand?

How Do You Become What You Cannot Yet Understand?

True transformation carries you beyond what you currently understand.

True transformation carries you beyond what you currently understand.

True transformation carries you beyond what you currently understand.

October 19, 2025

October 19, 2025

October 19, 2025

Why?

Because transformation does not merely add new content to your mind, it reconfigures the very machinery of your knowing.

It reorders what stands out to you, reprioritizes what you care about, and reorients your choices and actions.

From your present perspective, the values and insights on the other side of your transformation are cognitively inaccessible. They lie in the unknown.

You cannot (in advance) fully grasp what a transformative experience will mean to you, what it will feel like, or even who you will become through it.

And so you cannot postpone action until understanding arrives.

Why?

Because in these cases, understanding is not the condition for transformation:

It is its consequence.

Whenever you feel the call to grow (toward a deeper way of being, a more integrated self) you are being called to act in the absence of complete comprehension.

So we are always in a state of not-yet-knowing, and yet we are always called to act.

To become someone we are not…

…yet.

And so the question emerges:

How do I commit to a future I cannot yet fully grasp?

The answer lies in an experiment with chimpanzees and children…

Experiment:

In the first phase of the experiment, a group of chimpanzees is presented with an opaque box. A scientist performs a complex sequence of actions (pressing buttons, pulling levers) and eventually, a piece of candy is released. The chimps watch once or twice, then successfully imitate the entire sequence to obtain the reward.

Next, a group of children is shown the same setup:

They, too, observe the scientist’s actions and accurately reproduce the full sequence.

So far, both groups behave similarly.

In the second phase, the same box is used, but now it is transparent:

It becomes visibly clear that only the final action causes the candy to be released; the preceding steps are causally irrelevant.

The chimpanzees (after watching) quickly disregard the unnecessary actions and perform only the final one, efficiently securing the candy.

But the children?

They watch the scientist repeat all the redundant steps and despite their obvious uselessness… they imitate every single one of them again.

At first glance, it might appear that the chimps are smarter.

But something far more profound is happening in the children’s behavior:

They’re placing a bet.

They intuitively assume that adult acts with purpose, even if that purpose is not immediately intelligible to them. They trust that the adult’s behavior embodies a perspective they cannot yet access, but might come to understand by enacting it.

(If you want to watch the experiment: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JwwclyVYTkk)

This is the heart of aspirational learning:

As Agnes Callard describes, it is the kind of learning driven not by what you already value, but by a longing to become the kind of person who can value what is currently beyond your comprehension.

It is a recognition that your present standpoint is not the totality of all that can matter, and that others (those further along a developmental arc) may already inhabit a richer mode of being.

And this doesn’t end in childhood:

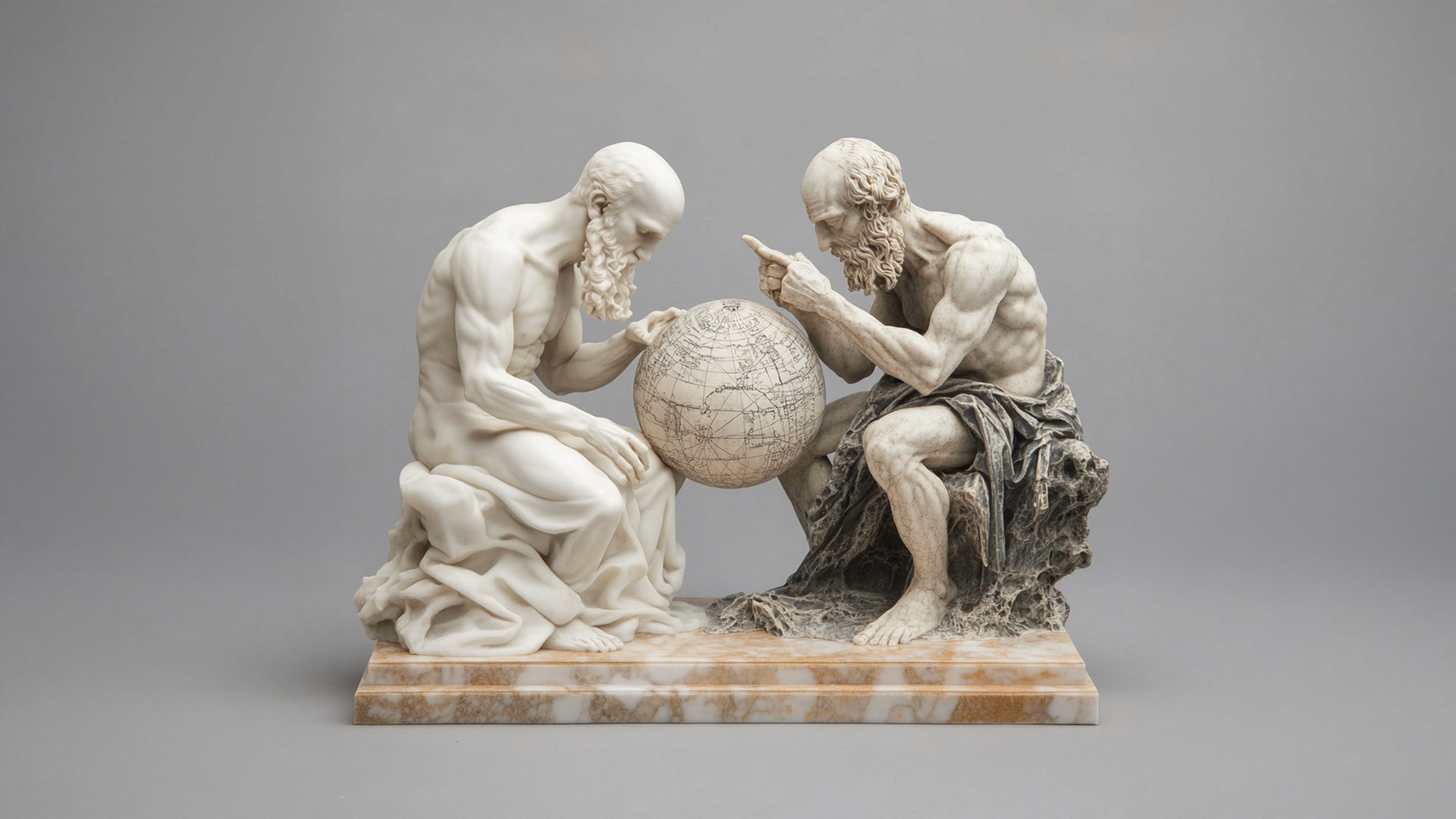

As the child is to the adult, the adult is to the sage.

It is in this sense that figures like Socrates, the Buddha, or Christ can become living patterns of aspirational identity.

Not because we worship them (nor because we blindly obey them) but because their lives enact a form of care, attention, and agency that discloses a different orientation toward what is real.

When someone like Antisthenes says, “I learned how to dialog with myself as if with Socrates,” he is naming the transformation of his inner speech.

He has taken Socrates not as an external authority; but as an inner structure of reflective thought. Socrates becomes an internalized presence that allows Antisthenes to engage in self-examination, self-correction, and the pursuit of greater alignment with the real.

This is a shift in participatory and perspectival knowing.

And the pattern of internalizing a trusted perspective also appears in the practical domain of sports psychology, as seen in the work of Nick Winkelman.

Athletes do not merely obey their coaches' instructions:

They are taking into their cognition and consciousness the perspective, style of attention, and way of acting of their coach.

They begin to simulate the presence of the coach within their own awareness:

“What would my coach notice about my movement right now?”

That internalized dialogue reshapes their salience landscape in real time. It reorganizes what stands out as relevant, what calls for adjustment, what possibilities for action (affordances) are perceived.

This is precisely the same dynamic at the core of aspirational learning:

When we engage with figures (like Socrates, the Buddha, or Christ) we are not simply mimicking external behaviors:

After all, we do not see them, physically, in the way the children saw the adults in the earlier experiment.

We are enacting their underlying patterns of attention, care, and agency.

We are taking up a way of being-in-the-world that reorients our salience landscape and reshapes our capacity to care about what truly matters.

Over time, they cease to function as distant authorities and instead become internalized structures of aspiration (simulated presences that guide our perception, direct our intentions) and cultivate our growth from within. They become part of the ongoing dialogue we have with ourselves as we navigate the complexities of transformation.

This is why (in the project of transformative development) you require patterns of being you can trust before you can fully explain them, because explanations arise from within a frame of understanding, and transformation (by its very nature) is a migration from one frame to another.

This is why the pattern must be trusted before it can be articulated: Because the transformation precedes the comprehension.

Why?

Because transformation does not merely add new content to your mind, it reconfigures the very machinery of your knowing.

It reorders what stands out to you, reprioritizes what you care about, and reorients your choices and actions.

From your present perspective, the values and insights on the other side of your transformation are cognitively inaccessible. They lie in the unknown.

You cannot (in advance) fully grasp what a transformative experience will mean to you, what it will feel like, or even who you will become through it.

And so you cannot postpone action until understanding arrives.

Why?

Because in these cases, understanding is not the condition for transformation:

It is its consequence.

Whenever you feel the call to grow (toward a deeper way of being, a more integrated self) you are being called to act in the absence of complete comprehension.

So we are always in a state of not-yet-knowing, and yet we are always called to act.

To become someone we are not…

…yet.

And so the question emerges:

How do I commit to a future I cannot yet fully grasp?

The answer lies in an experiment with chimpanzees and children…

Experiment:

In the first phase of the experiment, a group of chimpanzees is presented with an opaque box. A scientist performs a complex sequence of actions (pressing buttons, pulling levers) and eventually, a piece of candy is released. The chimps watch once or twice, then successfully imitate the entire sequence to obtain the reward.

Next, a group of children is shown the same setup:

They, too, observe the scientist’s actions and accurately reproduce the full sequence.

So far, both groups behave similarly.

In the second phase, the same box is used, but now it is transparent:

It becomes visibly clear that only the final action causes the candy to be released; the preceding steps are causally irrelevant.

The chimpanzees (after watching) quickly disregard the unnecessary actions and perform only the final one, efficiently securing the candy.

But the children?

They watch the scientist repeat all the redundant steps and despite their obvious uselessness… they imitate every single one of them again.

At first glance, it might appear that the chimps are smarter.

But something far more profound is happening in the children’s behavior:

They’re placing a bet.

They intuitively assume that adult acts with purpose, even if that purpose is not immediately intelligible to them. They trust that the adult’s behavior embodies a perspective they cannot yet access, but might come to understand by enacting it.

(If you want to watch the experiment: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JwwclyVYTkk)

This is the heart of aspirational learning:

As Agnes Callard describes, it is the kind of learning driven not by what you already value, but by a longing to become the kind of person who can value what is currently beyond your comprehension.

It is a recognition that your present standpoint is not the totality of all that can matter, and that others (those further along a developmental arc) may already inhabit a richer mode of being.

And this doesn’t end in childhood:

As the child is to the adult, the adult is to the sage.

It is in this sense that figures like Socrates, the Buddha, or Christ can become living patterns of aspirational identity.

Not because we worship them (nor because we blindly obey them) but because their lives enact a form of care, attention, and agency that discloses a different orientation toward what is real.

When someone like Antisthenes says, “I learned how to dialog with myself as if with Socrates,” he is naming the transformation of his inner speech.

He has taken Socrates not as an external authority; but as an inner structure of reflective thought. Socrates becomes an internalized presence that allows Antisthenes to engage in self-examination, self-correction, and the pursuit of greater alignment with the real.

This is a shift in participatory and perspectival knowing.

And the pattern of internalizing a trusted perspective also appears in the practical domain of sports psychology, as seen in the work of Nick Winkelman.

Athletes do not merely obey their coaches' instructions:

They are taking into their cognition and consciousness the perspective, style of attention, and way of acting of their coach.

They begin to simulate the presence of the coach within their own awareness:

“What would my coach notice about my movement right now?”

That internalized dialogue reshapes their salience landscape in real time. It reorganizes what stands out as relevant, what calls for adjustment, what possibilities for action (affordances) are perceived.

This is precisely the same dynamic at the core of aspirational learning:

When we engage with figures (like Socrates, the Buddha, or Christ) we are not simply mimicking external behaviors:

After all, we do not see them, physically, in the way the children saw the adults in the earlier experiment.

We are enacting their underlying patterns of attention, care, and agency.

We are taking up a way of being-in-the-world that reorients our salience landscape and reshapes our capacity to care about what truly matters.

Over time, they cease to function as distant authorities and instead become internalized structures of aspiration (simulated presences that guide our perception, direct our intentions) and cultivate our growth from within. They become part of the ongoing dialogue we have with ourselves as we navigate the complexities of transformation.

This is why (in the project of transformative development) you require patterns of being you can trust before you can fully explain them, because explanations arise from within a frame of understanding, and transformation (by its very nature) is a migration from one frame to another.

This is why the pattern must be trusted before it can be articulated: Because the transformation precedes the comprehension.

Why?

Because transformation does not merely add new content to your mind, it reconfigures the very machinery of your knowing.

It reorders what stands out to you, reprioritizes what you care about, and reorients your choices and actions.

From your present perspective, the values and insights on the other side of your transformation are cognitively inaccessible. They lie in the unknown.

You cannot (in advance) fully grasp what a transformative experience will mean to you, what it will feel like, or even who you will become through it.

And so you cannot postpone action until understanding arrives.

Why?

Because in these cases, understanding is not the condition for transformation:

It is its consequence.

Whenever you feel the call to grow (toward a deeper way of being, a more integrated self) you are being called to act in the absence of complete comprehension.

So we are always in a state of not-yet-knowing, and yet we are always called to act.

To become someone we are not…

…yet.

And so the question emerges:

How do I commit to a future I cannot yet fully grasp?

The answer lies in an experiment with chimpanzees and children…

Experiment:

In the first phase of the experiment, a group of chimpanzees is presented with an opaque box. A scientist performs a complex sequence of actions (pressing buttons, pulling levers) and eventually, a piece of candy is released. The chimps watch once or twice, then successfully imitate the entire sequence to obtain the reward.

Next, a group of children is shown the same setup:

They, too, observe the scientist’s actions and accurately reproduce the full sequence.

So far, both groups behave similarly.

In the second phase, the same box is used, but now it is transparent:

It becomes visibly clear that only the final action causes the candy to be released; the preceding steps are causally irrelevant.

The chimpanzees (after watching) quickly disregard the unnecessary actions and perform only the final one, efficiently securing the candy.

But the children?

They watch the scientist repeat all the redundant steps and despite their obvious uselessness… they imitate every single one of them again.

At first glance, it might appear that the chimps are smarter.

But something far more profound is happening in the children’s behavior:

They’re placing a bet.

They intuitively assume that adult acts with purpose, even if that purpose is not immediately intelligible to them. They trust that the adult’s behavior embodies a perspective they cannot yet access, but might come to understand by enacting it.

(If you want to watch the experiment: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JwwclyVYTkk)

This is the heart of aspirational learning:

As Agnes Callard describes, it is the kind of learning driven not by what you already value, but by a longing to become the kind of person who can value what is currently beyond your comprehension.

It is a recognition that your present standpoint is not the totality of all that can matter, and that others (those further along a developmental arc) may already inhabit a richer mode of being.

And this doesn’t end in childhood:

As the child is to the adult, the adult is to the sage.

It is in this sense that figures like Socrates, the Buddha, or Christ can become living patterns of aspirational identity.

Not because we worship them (nor because we blindly obey them) but because their lives enact a form of care, attention, and agency that discloses a different orientation toward what is real.

When someone like Antisthenes says, “I learned how to dialog with myself as if with Socrates,” he is naming the transformation of his inner speech.

He has taken Socrates not as an external authority; but as an inner structure of reflective thought. Socrates becomes an internalized presence that allows Antisthenes to engage in self-examination, self-correction, and the pursuit of greater alignment with the real.

This is a shift in participatory and perspectival knowing.

And the pattern of internalizing a trusted perspective also appears in the practical domain of sports psychology, as seen in the work of Nick Winkelman.

Athletes do not merely obey their coaches' instructions:

They are taking into their cognition and consciousness the perspective, style of attention, and way of acting of their coach.

They begin to simulate the presence of the coach within their own awareness:

“What would my coach notice about my movement right now?”

That internalized dialogue reshapes their salience landscape in real time. It reorganizes what stands out as relevant, what calls for adjustment, what possibilities for action (affordances) are perceived.

This is precisely the same dynamic at the core of aspirational learning:

When we engage with figures (like Socrates, the Buddha, or Christ) we are not simply mimicking external behaviors:

After all, we do not see them, physically, in the way the children saw the adults in the earlier experiment.

We are enacting their underlying patterns of attention, care, and agency.

We are taking up a way of being-in-the-world that reorients our salience landscape and reshapes our capacity to care about what truly matters.

Over time, they cease to function as distant authorities and instead become internalized structures of aspiration (simulated presences that guide our perception, direct our intentions) and cultivate our growth from within. They become part of the ongoing dialogue we have with ourselves as we navigate the complexities of transformation.

This is why (in the project of transformative development) you require patterns of being you can trust before you can fully explain them, because explanations arise from within a frame of understanding, and transformation (by its very nature) is a migration from one frame to another.

This is why the pattern must be trusted before it can be articulated: Because the transformation precedes the comprehension.

John Vervaeke, Ethan Hsieh & David Kemper

John Vervaeke, Ethan Hsieh & David Kemper

John Vervaeke, Ethan Hsieh & David Kemper

Latest Course

Generations of Joy

The Cognitive Science of Wellbeing and Happiness

Latest Course

Generations of Joy

The Cognitive Science of Wellbeing and Happiness

Latest Course

Generations of Joy

The Cognitive Science of Wellbeing and Happiness

More insights for you.

More insights for you.

More insights for you.

Explore more of the science and philosophy here.

Explore more of the science and philosophy here.

Explore more of the science and philosophy here.

Your questions.

Answered.

Not sure what to expect? These answers might help you feel more confident as you begin.

Didn’t find your answer? Send us a message — we’ll respond with care and clarity.

What if I’m not familiar with philosophy or science?

Yes! Our courses are designed to be accessible to both beginners and those with experience. John will hold a seminar after each lecture to answer any questions you might have.

What if I’m not familiar with philosophy or science?

Yes! Our courses are designed to be accessible to both beginners and those with experience. John will hold a seminar after each lecture to answer any questions you might have.

Do I need to have specific religious or scientific beliefs to benefit from the course?

Do I need to have specific religious or scientific beliefs to benefit from the course?

No. The courses are open to everyone, regardless of religious or scientific background. It’s about exploring diverse perspectives and finding a way to integrate them into your life.

Will this course challenge my current beliefs?

Will this course challenge my current beliefs?

Yes, the course is designed to provoke deep reflection. It introduces perspectives that will encourage you to question and reconsider long-held beliefs, fostering growth and deeper understanding.

I’m worried I won’t understand the material. Is it too advanced?

I’m worried I won’t understand the material. Is it too advanced?

Not at all! The course breaks down complex ideas into simple, easy-to-understand concepts, ensuring that whether you’re new to philosophy or well-versed, you’ll gain valuable insights.

What if I can’t attend live sessions or keep up with the pace?

What if I can’t attend live sessions or keep up with the pace?

All materials, including live session recordings, will be available to you anytime. You can go through the content at your own pace, fitting it around your schedule.

Is there any interaction with the instructor or other students?

Is there any interaction with the instructor or other students?

Yes! You will have the opportunity to engage with John and fellow students throughout the course.

Your questions.

Answered.

Not sure what to expect? These answers might help you feel more confident as you begin.

What if I’m not familiar with philosophy or science?

Yes! Our courses are designed to be accessible to both beginners and those with experience. John will hold a seminar after each lecture to answer any questions you might have.

What if I’m not familiar with philosophy or science?

Yes! Our courses are designed to be accessible to both beginners and those with experience. John will hold a seminar after each lecture to answer any questions you might have.

Do I need to have specific religious or scientific beliefs to benefit from the course?

Do I need to have specific religious or scientific beliefs to benefit from the course?

No. The courses are open to everyone, regardless of religious or scientific background. It’s about exploring diverse perspectives and finding a way to integrate them into your life.

Will this course challenge my current beliefs?

Will this course challenge my current beliefs?

Yes, the course is designed to provoke deep reflection. It introduces perspectives that will encourage you to question and reconsider long-held beliefs, fostering growth and deeper understanding.

I’m worried I won’t understand the material. Is it too advanced?

I’m worried I won’t understand the material. Is it too advanced?

Not at all! The course breaks down complex ideas into simple, easy-to-understand concepts, ensuring that whether you’re new to philosophy or well-versed, you’ll gain valuable insights.

What if I can’t attend live sessions or keep up with the pace?

What if I can’t attend live sessions or keep up with the pace?

All materials, including live session recordings, will be available to you anytime. You can go through the content at your own pace, fitting it around your schedule.

Is there any interaction with the instructor or other students?

Is there any interaction with the instructor or other students?

Yes! You will have the opportunity to engage with John and fellow students throughout the course.

Didn’t find your answer? Send us a message — we’ll respond with care and clarity.

Your questions.

Answered.

Not sure what to expect? These answers might help you feel more confident as you begin.

Didn’t find your answer? Send us a message — we’ll respond with care and clarity.

What if I’m not familiar with philosophy or science?

Yes! Our courses are designed to be accessible to both beginners and those with experience. John will hold a seminar after each lecture to answer any questions you might have.

What if I’m not familiar with philosophy or science?

Yes! Our courses are designed to be accessible to both beginners and those with experience. John will hold a seminar after each lecture to answer any questions you might have.

Do I need to have specific religious or scientific beliefs to benefit from the course?

Do I need to have specific religious or scientific beliefs to benefit from the course?

No. The courses are open to everyone, regardless of religious or scientific background. It’s about exploring diverse perspectives and finding a way to integrate them into your life.

Will this course challenge my current beliefs?

Will this course challenge my current beliefs?

Yes, the course is designed to provoke deep reflection. It introduces perspectives that will encourage you to question and reconsider long-held beliefs, fostering growth and deeper understanding.

I’m worried I won’t understand the material. Is it too advanced?

I’m worried I won’t understand the material. Is it too advanced?

Not at all! The course breaks down complex ideas into simple, easy-to-understand concepts, ensuring that whether you’re new to philosophy or well-versed, you’ll gain valuable insights.

What if I can’t attend live sessions or keep up with the pace?

What if I can’t attend live sessions or keep up with the pace?

All materials, including live session recordings, will be available to you anytime. You can go through the content at your own pace, fitting it around your schedule.

Is there any interaction with the instructor or other students?

Is there any interaction with the instructor or other students?

Yes! You will have the opportunity to engage with John and fellow students throughout the course.